'Palestine Belongs to the Arabs', said Gandhi.

A short note on the Palestinian Revolt of 1936 and India.

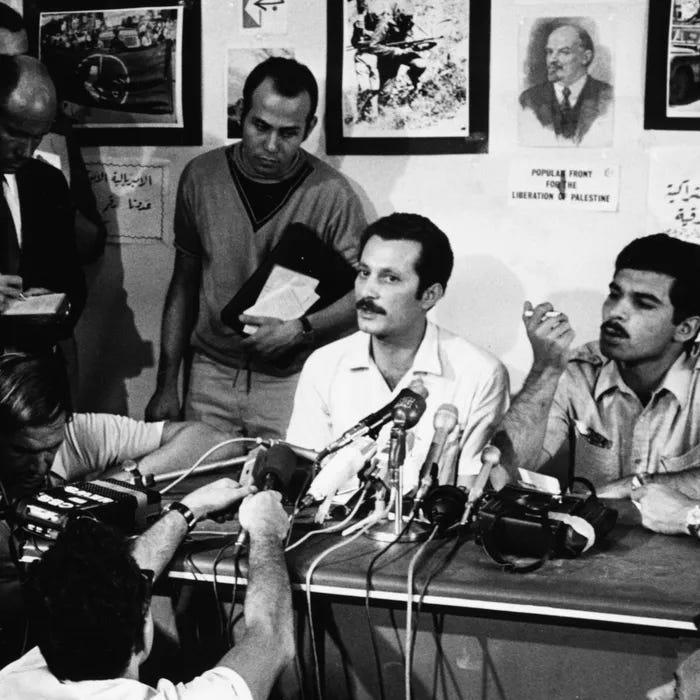

In 1936, peasants and workers revolted in Palestine against British rule as well as the sale of land to Jewish settlers and the zu’ama (political bosses) of Palestine. It was a major uprising that lingered for three years, before being crushed by the British. The best account of this revolt was written by our comrade Ghassan Kanafani (and recently published in a new translation by 1804 Books).

Palestinians looked to India for inspiration; as the great Palestinian poet Ibrahim Abd al-Fattah Tuqan wrote in 1929:

If only one of our leaders would fast like Gandhi – perhaps his fast would do some good. There is no need for him to abstain from food – in Palestine a leader would die without food. Let him abstain from selling land, and keep a plot in which to lay his bones.

During the Revolt in Palestine, the Indian National Congress carefully studied the events in West Asia. Sympathy with the Arabs was instinctive, since the Arabs were under British colonial rule and they were being forced to surrender their land to Jewish settlers. On 31 October 1937, the Indian National Congress took a firm position against ‘the reign of terror’ by British imperialists and Jewish terrorists – such as in the Haganah – and offered the solidarity of the Indians to the Palestinians ‘in their struggle for national freedom’.

The calculation for this position was made clear the next year by Gandhi. ‘My sympathies are with the Jews’, he wrote on 26 November 1938. ‘But my sympathy does not bind me to the requirements of justice’. For Gandhi, ‘Palestine belongs to the Arabs’ and ‘surely it would be a crime against humanity to reduce the proud Arabs so that Palestine can be restored to the Jews partly or wholly as their national home’.

Here are the main concepts at work – imperialism, anti-colonial nationalism, and anti-racism. There was no anti-Semitism at work here, none of the ideas that would lead to the Holocaust. Such ideas, marinating in Germany and in others parts of Europe, would find their home within India in the sewers of Hindutva - the political form that did mimic European nationalism’s narrowness. It produced people like RSS leader M. S. Golwalkar, who wrote in 1939 of how Hitler’s Germany - rightly - to his mind was ‘purging the country of Semitic races – the Jews. National pride at its highest has been manifested here. Germany has shown how well-nigh impossible it is for races and cultures, having differences going to the root, to be assimilated into one united whole, a good lesson for us in Hindustan to learn and profit by’.

But this was not the lesson learnt by the broad stream of the national movement that included the Indian National Congress, the socialists, and the communists. They did not accept the fascism of Hindutva nor of Germany’s Nazis. It adopted a policy drawn from its anti-colonial nationalism, from its genuine anti-fascist politics. There is a straight line from this form of anti-colonialism to the decision by the 16 million member All-India Kisan Sabha (the farmers’ union) to support BDS (boycott-divestment-sanctions) in 2017.

It was one thing for the freedom movement to take this position in the 1930s, but it was another to do something about it. India could give no tangible support to the Palestinians at this time. Colonial rule prevented the delivery of direct aid. This would change with the support that the Indian freedom movement was able to provide in Spain to defend the Republic (as I will write in another post).

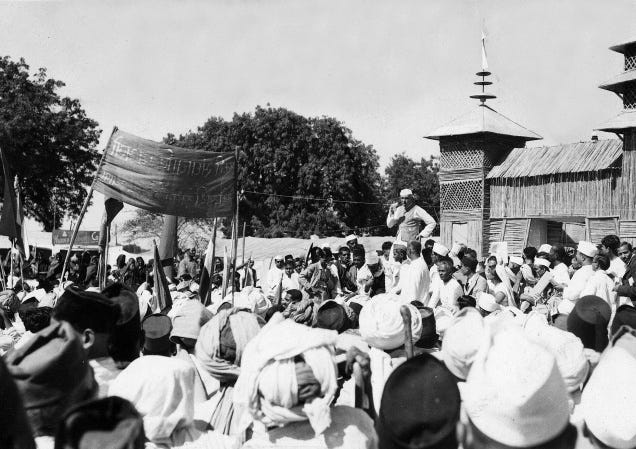

The freedom movement did however conduct activities to build support within India for Palestine. The Congress declared that 27 September 1936 would be celebrated as Palestine Day. Nehru led mass rallies in support of Palestine. In Allahabad, his home town, Nehru told a large crowd, ‘Our sympathies and good wishes must go to the people of Palestine in this hour of their distress. The crushing of their movement is a blow to our national struggle as well as to theirs. We hang together in this world struggle for freedom’. Once more the brutality of the British response irked Nehru. ‘The whole Arab world is aflame with indignation and the East - Muslims and non-Muslims alike - has been deeply affected by this brutal attempt to crush a people struggling for their freedom’. Palestine Day was observed again on 26 August 1938 - with the Congress and the Left fully behind the Palestinians and against the partition of their country.

It was the most that the Indians could do. The British did not allow passage of supplies of any kind to Palestine. They created a wall against the solidarity that was clearly on display from the Indian nationalists towards the struggle of the Palestinians against colonial fascism.

This shows the dangers of selective quotation. “My sympathy is with the Jews” is often cited by Zionists as proof of Gandhi’s solidarity. They, of course, leave off the next sentence. The brutality and racism of the British, and Churchill, are well known, yet Gandhi prevailed. I would like to know how historians assess the failure of passive resistance against the IDF, most notably the March of Return in 2018. What would Gandhi have done? Is passive resistance futile against an enemy with no conscience?

He said this too.

He had no sympathy to Hindus or Sikhs.

Should we follow this also?