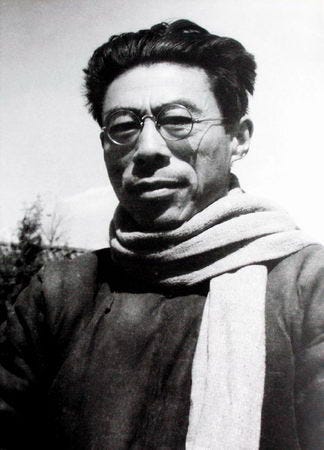

Spending time on the Tsinghua University campus, thanks to the Institute of Advanced Study in the Humanities (and its director Professor Wang Hui and Professor Yan Hairong), has been a release. I have been able to interact with students, learn from them and their rich projects, use the library, and walk amongst the flowering trees in the midst of beautiful Beijing. I often walk past the statue of Wen Yiduo (1899-1946), not giving a second thought to it because it is on the path of my walk from the library to my room.

But, on Sunday, I decided to spend some time with him.

I did so on a lark. I had been in the library researching the Indian doctors who came to join the anti-Japanese war in 1938, and when I left the reading area, it was sunny outside, and there were children playing all over the grounds of the university. It is remarkably democratic space, the entire campus open to the people of Beijing to come and treat it as their playground. I thought Wen Yiduo, smoking his pipe, would enjoy the chaos.

A student at Tsinghua, and a young poet, he left China in 1922 to study fine arts at the Art Institute of Chicago. It was there that he put together his first collection of poems - Hongzhu (紅燭, Red Candle).

During his time in Chicago, he wrote a lovely poem, an ode to a hard work of the Chinese laundry workers:

Don’t you Americans worry that the job is vile

Just find where it is not clean or smooth, and

Call the Chinaman, call the Chinaman.

I can clean handkerchiefs soaked with tears

I can whiten sweaters black with crime,

Grease of greed, dirt of desire

And all the filthy things you have at home.

When Wen Yidou returned to China in 1925, he joined the Crescent Moon Society, a poetry group set up by Xu Zhimo (1897-1931). The society was named after a book of poems published by Rabindranath Tagore in 1913. Xu had been the interpreter for Tagore when he came to China in 1924, so he drew from that inspiration for the name of the society.

That is Tagore with Xu Zhimo and the other host for his trip, Lin Huiyin (1904-1955), one of the first women architects in China (she was one of the designers of the emblem of the People’s Republic of China)

Within the society, and under its influence, Wen continued to write poetry, influenced by his deep learning of classical Chinese poetry and his desire for change in his country.

This stagnant ditch is hopeless.

Clearly, not a place where beauty thrives.

Better cultivate its ugliness.

Perhaps its ugliness will create a world.

Wen did not write many poems after 1928. He became more of a critic, but was also absorbed into the political maelstrom of the time. Due to the Japanese advances into central China, Wen moved to Kunming and joined the Communist-affiliated Chinese Democratic League.

On 12 July 1946, Wen’s friend Li Gongpu (1902-1946) was assassinated by Kuomintang agents. Li was another interesting man, who had gone undercover in 1928 to expose labour conditions in Alaskan canneries (when he was a student at Reed College), and who was one of the founders of the Chinese Democratic League.

Three days later, on 15 July, Wen went to a rally for Li and spoke with great passion about his friend and against the Kuomintang. Wen was shot to death that afternoon.

It might be nice to remember the great poet and revolutionary with his words from Miracle:

In reality, I've always loathed

that dirty business—constructing those lavish

farfetched glosses. What I want is clarity,

the direct word.

I cannot express how much I value these vignettes into worlds that I otherwise might never see. It’s a great gift after reading dreary news reports all afternoon, and wondering if I will outlive my country by a fraction of a second.

Utterly speechless to learn about the poet and his journey, his fortituous encounter with Tagore, his revolutionary friendship and death... and to think that all of this historical gems are unearthed from a foreign language library within a handful of trips! 🤯