The sense of danger must not disappear:

The way is certainly both short and steep,

However gradual it looks from here;

Look if you like, but you will have to leap.W. H. Auden, 1940.

On 16 September, the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) will celebrate its second anniversary. Two years ago, the governments of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger came together to form the AES to do two things: first, to protect themselves from what appeared to be an imminent attack from US and French backed military forces from neighbouring countries, and second, to use their combined resources to proceed down the road to defeat the terrorist forces in the north of their countries and to address the pressing needs fo their people. The AES succeeded in the first instance: its formation stayed the hand of the neighbouring countries from attempting a precipitous invasion of any one of them, since they had signed a mutual defence pact. The second promise of the AES is going to take more time, given that the terrorist groups are entrenched in parts of their territory and have taken hold of important trade routes, and given that development is not an overnight process, but takes time. Each of these states has the right to celebrate the formation of the AES, but its real impact has not yet been felt since that will take at least a decade if not longer.

Before the pandemic, I visited the Sahel region twice, going to explore the web of US and French military bases in the region, and to report on the growing crisis of mostly West African migrants trying to cross the Sahara Desert and get to Europe. I could learn much about the bases, since the Men of the Bases keep to themselves and do not disclose much to strangers. They typically lived on them, having their basic sustenance flown in from abroad, and when they left the bases, it was in large convoys to go and do what foreign soldiers do on what they rightly see as hostile territory. I ran into a few protests outside bases, but these were small and would only expand into major protests after the pandemic and alongside the cascade of military coups that overthrew the rather hapless collaborating governments in each of these three countries. It was much easier to track the migration, both from Niger and from Libya. I want to share one of my reports, which I published in 2017 in The Hindu (and now exists behind a paywall).

Refugees do not show up in the Mediterranean Sea as if from no-where. By the time they get into their flimsy boats on the Libyan coastline, they have lived many, many dangerous lives. They would have left their increasingly unproductive fields in western and eastern Africa, fled wars in the Horn of Africa, in Sudan and in places as far as Afghanistan, and travelled over great distances to get to what they see as the final leg of their journey. What they want is to make it to Europe, which – since the early days of colonialism – has broadcast itself as the land of milk and honey. Old colonial ideas and the wealth of Europe built from colonial labour beckons. It is a siren for the wretched of the earth. It has ended for many Africans in virtual concentration camps in Libya, where refugees that Europe does not want now linger – some sold into slavery.

To get to Libya, the migrants and refugees have to cross the forbidding Sahara Desert, which in Arabic is known – rightly – as the Greatest Desert (al-Sahara al-Kubra). It is vast, hot and dangerous. Old salt caravans – the Azalai - mostly managed by the Tuareg peoples would run between Mali as well as Niger and Libya. They would carry gold, salt, weapons and captured human beings as objects of trade. Those old caravans still make their journey, moving from one water source to the next, the camels as exhausted as the Tuareg. Newer caravans have supplanted these older ones. Camels are not their mode of transport. They prefer buses, pickup trucks and jeeps to ferry humans and cocaine towards Europe, while guns and money comes southwards. These newer caravans drive along unmarked paths, heading between sand dunes, searching for old tire tracks that have been buried in disorienting sandstorms.

The Sahara is dangerous. The journey in a pickup truck could take three days, at best, or the refugees and cocaine mules could find themselves dying from dehydration, extremists, smugglers or the security forces in the region. There are many people ready to prey on the travellers and on the smugglers, whose cars are routinely stolen. No proper account exists of dead refugees. This June, the UN Refugees Agency reported the death of 44 migrants who died of dehydration and heat stroke when their truck broke down between the Nigerien cities of Agadez and Dirkou. The UN had saved at least 600 migrants in the three months between April and June. ‘Saving lives in the desert is becoming more urgent than ever’, said Giuseppe Loprete who is the Niger Chief of Mission for the International Organisation for Migration.

To prevent the migrants from reaching the Mediterranean, France has asked five African countries (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger) to join its G5 Sahel Initiative. The Sahel is the belt that runs across Africa below the Sahara Desert. The European Union has also contributed to this project. The Europeans want to move their southern border from the northern edge of the Mediterranean Sea to the southern rim of the Sahara Desert. French military bases run across the Sahel, as the United States builds an enormous base in Agadez (Niger) from where it will fly drones to provide aerial support. The military has arrived in the Sahel to stop the flow of migrants.

Agadez, where the United States military is spending $100 million to build its drone base, sits at the crossroads of our contemporary crises. Refugees come to it in desperation – their land made miserable by trade policies that discriminate against small farmers and by desertification caused by carbon capitalism. As the United States government has made it difficult for cocaine to enter the US from Central America, the cocaine mafia have moved its operations to this central belt of Africa. A leading politician in Niger – Cherif Ould Abidine – who died in 2016 was known as Mr. Cocaine. Billions of dollars of cocaine now moves through the Sahel into the Sahara and upwards to Europe. The pickup trucks that carry refugees and cocaine go past the town of Arlit, where French multinational corporations are harvesting uranium (Oxfam noted in 2013, ‘One of every three light bulbs in France is lit thanks to Nigerien uranium’). So here we have it: refugees, cocaine, uranium and a massive military enterprise.

Men from Gambia and from Mali wait outside a smugglers’ compound. His Toyota Hilux, the camel of this new trade, sits near the gate. The men are wearing sunglasses. This is their defence once they enter the desert. They are apprehensive. Their future – however grim – must be better than their present. These are gamblers. They are willing to take the chance. The engine fires up. They throw their modest belonging onto the truck. It is time for their azalai.

Saïdou Dicko (Burkina Faso), The Water Statue, 2020.

Then, in 2024, I returned to the story, with a glance at the Sahara from Libya. Here is that story:

Sabah, Libya, is an oasis town at the northern edge of the Sahara Desert. To stand at the edge of the town and look southward into the desert toward Niger is forbidding. The sand stretches past infinity, and if there is a wind, it lifts the sand to cover the sky. Cars come down the road past the al-Baraka Mosque into the town. Some of these cars come from Algeria (although the border is often closed) or from Djebel al-Akakus, the mountains that run along the western edge of Libya. Occasionally, a white Toyota truck filled with men from the Sahel region of Africa and from western Africa makes its way into Sabah. Miraculously, these men have made it across the desert, which is why many of them clamber out of their truck and fall to the ground in desperate prayer. Sabah means ‘morning’ or ‘promise’ in Arabic, which is a fitting word for this town that grips the edge of the massive, growing, and dangerous Sahara.

For the past decade, the United Nations International Organisation of Migration (IOM) has collected data on the deaths of migrants. This Missing Migrants Project publishes its numbers each year, and so this April, it has released its latest figures. For the past ten years, the IOM says that 64,371 women, men, and children have died while on the move (half of them have died in the Mediterranean Sea). On average, each year since 2014, 4,000 people have died. However, in 2023, the number rose to 8,000. One in three migrants who flee a conflict zone die on the way to safety. These numbers, however, are grossly deflated, since the IOM simply cannot keep track of what they call ‘irregular migration’. For instance, the IOM admits, ‘[S]ome experts believe that more migrants die while crossing the Sahara Desert than in the Mediterranean Sea’.

Sandstorms and Gunmen

Abdel Salam, who runs a small business in the town, pointed out into the distance and said, ‘In that direction is Toummo’, the Libyan border town with Niger. He sweeps his hands across the landscape and says that in the region between Niger and Algeria is the Salvador Pass, and it is through that gap that drugs, migrants, and weapons move back and forth, a trade that enriches many of the small towns in the area, such as Ubari. With the erosion of the Libyan state since the NATO war in 2011, the border is largely porous and dangerous. It was from here that the al-Qaeda leader Mokhtar Belmokhtar moved his troops from northern Mali into the Fezzan region of Libya in 2013 (he was said to have been killed in Libya in 2015). It is also the area dominated by the al-Qaeda cigarette smugglers, who cart millions of Albanian-made Cleopatra cigarettes across the Sahara into the Sahel (Belmokhtar, for instance, was known as the ‘Marlboro Man’ for his role in this trade). An occasional Toyota truck makes its way toward the city. But many of them vanish into the desert, a victim of the terrifying sandstorms or of kidnappers and thieves. No one can keep track of these disappearances, since no one even knows that they have happened.

Matteo Garrone’s Oscar-nominated Io Capitano (2023) tells the story of two Senegalese boys—Seydou and Moussa—who go from Senegal to Italy through Mali, Niger, and then Libya, where they are incarcerated before they flee across the Mediterranean to Italy in an old boat. Garrone built the story around the accounts of several migrants, including Kouassi Pli Adama Mamadou (from Côte d’Ivoire, now an activist who lives in Caserta, Italy). The film does not shy away from the harsh beauty of the Sahara, which claims the lives of migrants who are not yet seen as migrants by Europe. The focus of the film is on the journey to Europe, although most Africans migrate within the continent (21 million Africans live in countries in which they were not born). Io Capitano ends with a helicopter flying above the ship as it nears the Italian coastline; it has already been pointed out that the film does not acknowledge racist policies that will greet Seydou and Moussa. What is not shown in the film is how European countries have tried to build a fortress in the Sahel region to prevent migration northwards.

Open-Air Tomb

More and more migrants have sought the Niger-Libya route after the fall of the Libyan state in 2011 and the crackdown on the Moroccan-Spanish border at Melilla and Ceuta. A decade ago, the European states turned their attention to this route, trying to build a European ‘wall’ in the Sahara against the migrants. The point was to stop the migrants before they get to the Mediterranean Sea, where they become an embarrassment to Europe. France, leading the way, brought together five of the Sahel states (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger) in 2014 to create the G5 Sahel. In 2015, under French pressure, the government of Niger passed Law 2015-36 that criminalised migration through the country. G5 Sahel and the law in Niger came alongside European Union funding to provide surveillance technologies—illegal in Europe—to be used in this band of countries against migrants. In 2016, the United States built the world’s largest drone base in Agadez, Niger, as part of this anti-migrant program. In May 2023, Border Forensics studied the paths of the migrants and found that due to the law in Niger and these other mechanisms the Sahara had become an ‘open-air tomb’.

Over the past few years, however, all of this has begun to unravel. The coup d’états in Guinea (2021), Mali (2021), Burkina Faso (2022), and Niger (2023) have resulted in the dismantling of G5 Sahel as well as the demand for the removal of French and US troops. In November 2023, the government of Niger revoked Law 2015-36 and freed those who had been accused of being smugglers.

Abdourahamane, a local grandee, stood beside the Grand Mosque in Agadez and talked about the migrants. ‘The people who come here are our brothers and sisters’, he said. ‘They come. They rest. They leave. They do not bring us problems’. The mosque, built of clay, bears within it the marks of the desert, but it is not transient. Abdourahamane told me that it goes back to the 16th century, long before modern Europe was born. Many of the migrants come here to get their blessings before they buy sunglasses and head across the desert, hoping that they make it through the sands and find their destiny somewhere across the horizon.

Now, the AES is on a new journey. Please read the texts below from Tricontinental: Institute of Social Research. It will help you understand the process underway in the Sahel, a distance from the austerity-debt-migration-war formation of imperialism.

1) The Sahel Seeks Sovereignty. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research: Dossier no. 91 (August 2025).

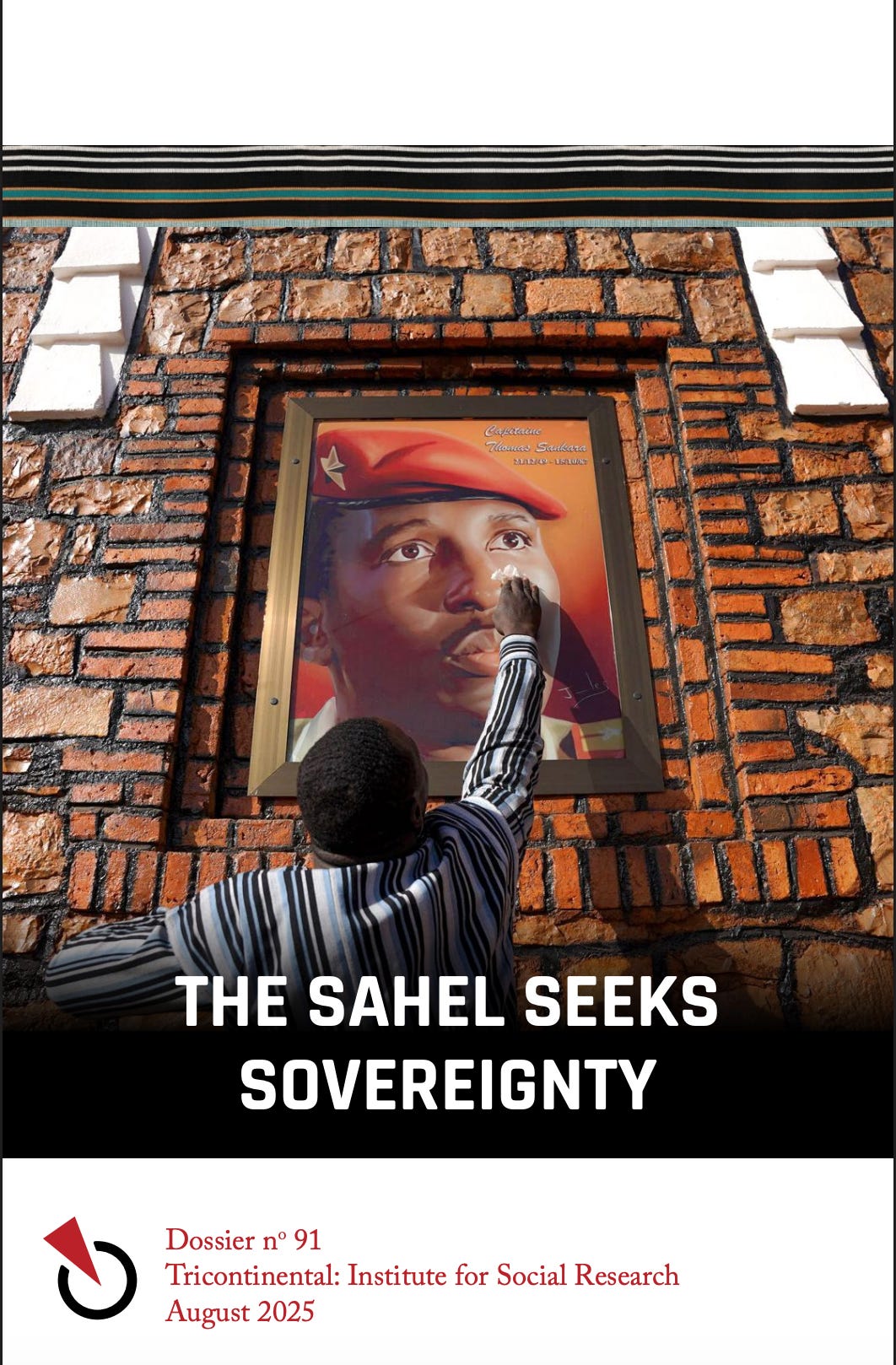

2) ‘Thomas Sankara’s Legacy is Alive in the Sahel’, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research: Newsletter 33 (14 August 2025).

Join the commemoration with the International Peoples Assembly on 16 September.

Thank you for helping me understand what is happening in this area, and the role so-called "Western" countries have played in their suffering.

https://open.substack.com/pub/paulokirk/p/i-cant-blame-the-allies-for-not-know?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=5i319