This is a series on my favourite journalists, people whose bravery I admire but also whom I admire for their honesty and their way of recounting the news as they have experienced it and analysed it. I hope this set of essays will continue till I have run through the list of those whose books I have before me, who inspire me to report, and to write.

#1 was on Odd Karsten Tveit, which you can read here.

#2 was on Wilfred Burchett, which you can read here.

One of the most interesting features of the Communist movement is the insistence on writing. This comes from the 19th century, when the trade union movement pushed for literacy campaigns within their ranks and built trade union schools to lift the clarity of their members. Trade union newspapers shaped the imagination of the workers to understand the world from their point of view. Workers not only had the paper read to them and read them, but they learned to write for their own paper. This was a legacy adopted wholesale by the Communists. Lenin’s What Is To Be Done? (1902) insisted on the importance of the newspaper, which had to be written by Communists – who would become reporters as well as theorists – and distributed by Communists. The newspaper was a way to bring together those around their country who were organising the workers and peasants and building their vanguard party. The paper was a point of information (to learn about what other workers were doing) and confidence (to take inspiration from these actions). Till today, the Communist movement puts the act of journalism near the centre of its work.

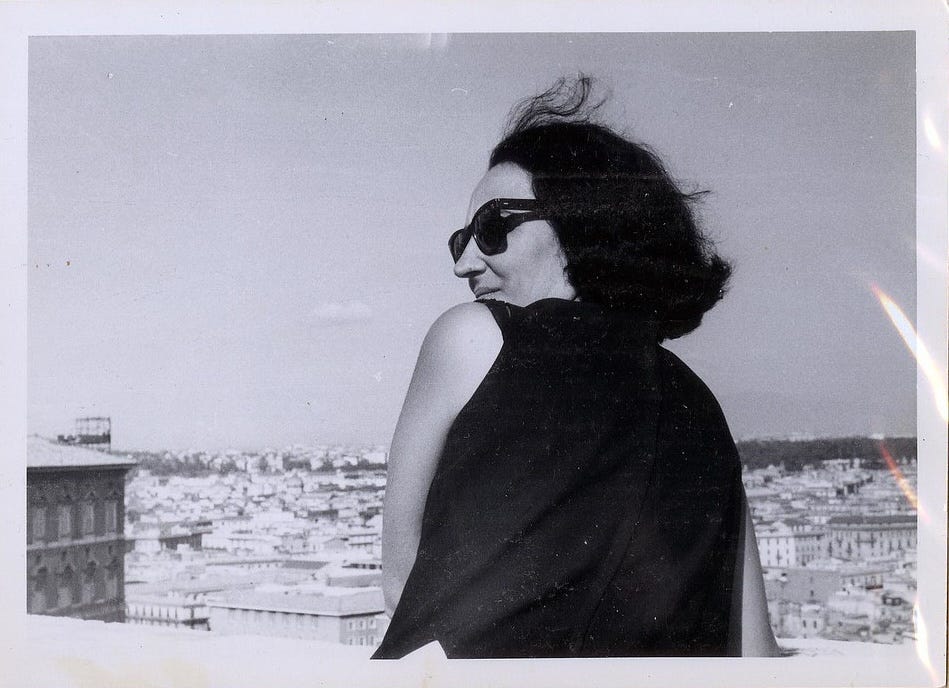

Ruth First (1925-1982) emerged into the South African Communist movement as a journalist. Julius First and Matilda Levetan, Ruth’s parents – Jewish migrants from Latvia – had been founding members of the Communist Party of South Africa in 1921, and of course they influenced their daughter. First briefly worked in the city government in Johannesburg, until she began her career as a journalist alongside her work as an active member of the Communist Party. She wrote for a series of communist-affiliated papers that went between legality and banning - The Guardian (1937-1952), New Age (1954-1962), and Fighting Talk (1954-1965) – writing a flurry of important texts, some signed and some unsigned, about the most compelling issue of her day – the anti-apartheid struggle, and, in particular, the role of working-class Black, Indian, and Coloured workers in this struggle.

One of her earliest and most powerful pieces of writing came when she visited a farm at Bethal in Mpumalanga. She interviewed Work Nyeiland (age 15) from Nyasaland (now Malawi).

When asked to describe conditions on the farm on which he works, he silently takes off his shirt to show large weals on his shoulders and aims. He explains he has scars whipped on his back, shoulders with a sjambok [a leather whip]. He cannot really explain why.

Recruiters for these farms found young boys who had tried to migrate without papers and were therefore vulnerable. In another report, First wrote about how the recruiters went to prisons to find workers:

Patrick Sebukulu is a 17-year-old African who was sentenced recently to a fine of £10 or two months imprisonment for being in possession of a dangerous weapon. But when his sister presented the £ 10 at the gaol she was told it was too late: he had been sold to a farmer at Köster and could not be released.

First’s reports are to be read alongside those of Henry Nxumalo (1917-1957), a sport’s reporter for the Drum, an African publication. In 1952, Nxumalo went underground to find out more about the kind of slave labour being employed in Bethal. He found out about white farmers such as Mabulala (The Killer) and Fakefutheni (Hit Him in the Marrow). The story he wrote in The Drum (March 1952) was published under the name of Mr. Drum. The news went around. ‘Bethalians are calling Drum “the emancipating magazine,”’ wrote a reader from Bethal, ‘and every literate of Bethal is buying it’. The story elicited a debate in parliament. Just a few years later, in 1957, Nxumalo was killed by unknown people while he was reporting on a story about abortion (there is a wonderful portrait of Nxumalo in Anthony Sampson’s Drum. A Venture into the New Africa, 1956).

The writings of Nxumalo and First brought the story to the South African Congress of Trade Unions, which began a potato boycott in May 1959 against ‘farm slavery’. In New Age on 4 June 1959, First covered how the National Anti-Pass Conference decided to boycott potatoes against the ‘horrifying conditions of farm labourers on the big potato farms in the Transvaal’. The boycott succeeded. The workers pushed forward the anti-apartheid movement (this is an element Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research emphasised in the dossier on the Durban Strikes of 1973 in the anti-apartheid fight, although the role of the workers goes back to the 1950s).

On 3 November 1955, New Age proclaimed: Pretoria Conquered by the women! This article by First focused on the massive protest by women against the pass laws that would not only restrict their movement but segregated women further along racial lines. Her description is vivid:

Indian women were there in their exquisite saris; Coloured women from the Coloured townships and the factories; a band of European women who did sterling work helping with transport arrangements. An old African woman, half-blind, brought her granddaughter to lead her. African churchwomen were there in their brilliant blue and white; women dingaka (herbalists) in their beads and skins with all regalia; smartly dressed and emancipated young factory workers; housewives and mothers; domestic servants and washerwomen; and, holding the delegations together and giving the great gathering that impressive discipline, the women Congress workers who started this protest rolling in the locations and townships some eight weeks ago when the Mother’s Congress first resolved on it.

Their leaders, Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi, Sophia Williams, and Rahima Moosa, went in to deliver their petition to the cry, Afrika, and then when they returned to the song, Inkosi Sikelele.

In New Age on 12 July 1956, First sensitively catalogued the way the pass laws and the apartheid system created structural unemployment for Black youth that turned the townships into places of gang violence. Then, in October 1956, Fighting Talk had her longer form study of how the pass laws set in motion a process of sending Black men to prison, ‘the new slavery’, for ‘violations’ of the laws, and then through the anxiety about the loss of the pass and the indignity of it, workers are ‘cowed, controlled, docile labour without the right to bargain for a better job, to compete in any labour area other than the one in which he is pegged as a work-seeker’. It was a system of humiliation for the worker and profit for the owners. First wrote firmly of slavery being abolished in South Africa in 1834, ‘but the pass laws still bind the African to his master, block his entry to the towns, keep him under constant police surveillance, control his movement, turn every employer into an arm of the police state, keep the migratory labour system going, and try to prevent the growth of stable, urban African communities in a modern industrialised society in which the old master-servant relations should be swept aside’. But they are not. The old racism is the new racism; the old economy is the new economy.

No-one took this lightly. On 1 August 1957, New Age carried her story on how ‘Anti-Pass protests shake the land’. The first paragraph is sufficient to get the idea: ‘Like those crackling veld fires that sweep over the dry Transvaal grass before the summer rains, the protest of African women against passes is spreading furiously from one area to another’.

On and on. The journalist did not stop. The great process of her age, the fight of ordinary people in South Africa against apartheid, had to be documented. The document was part of the struggle. It refused to allow the process to be disregarded, and it gave others the confidence to join the fight. She faced the hard edge of the Suppression of Communism Act of 1950 and the General Law Amendment Act of 1963. She was sent to prison for 117 days in 1963. It was then that she went into exile, ending the period of her ability to be a journalist of the struggle alongside the working-class and the peasantry.

Ruth First’s interview with Qaddafi.

In exile, First wrote a series of remarkable books, of which my favourites are:

· 117 Days (1965)

· The Barrel of a Gun (1970).

· Libya: The Elusive Revolution (1974).

· The Mozambican Miner (1977).

Extracts from these books can be found in the Tricontinental and International Union of Left Publishers - Ruth First: Selected Writings (2023).

On 17 August 1982, Ruth First was at her office at the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane in Maputo, Mozambique. A package had come for her. She opened it. It was a letter bomb sent by the South African Bureau of State Security (the bomb was dispatched by Craig Williamson, who later took responsibility). First died instantly. She was only fifty-seven.

First left behind her three children Shawn Slovo (born 1950), Gillian Slovo (born 1952), and Robyn Slovo (born 1953), and her husband, the communist leader Joe Slovo (1926-1995). And a bereft liberation struggle, which had relied upon her for her wisdom and writing.

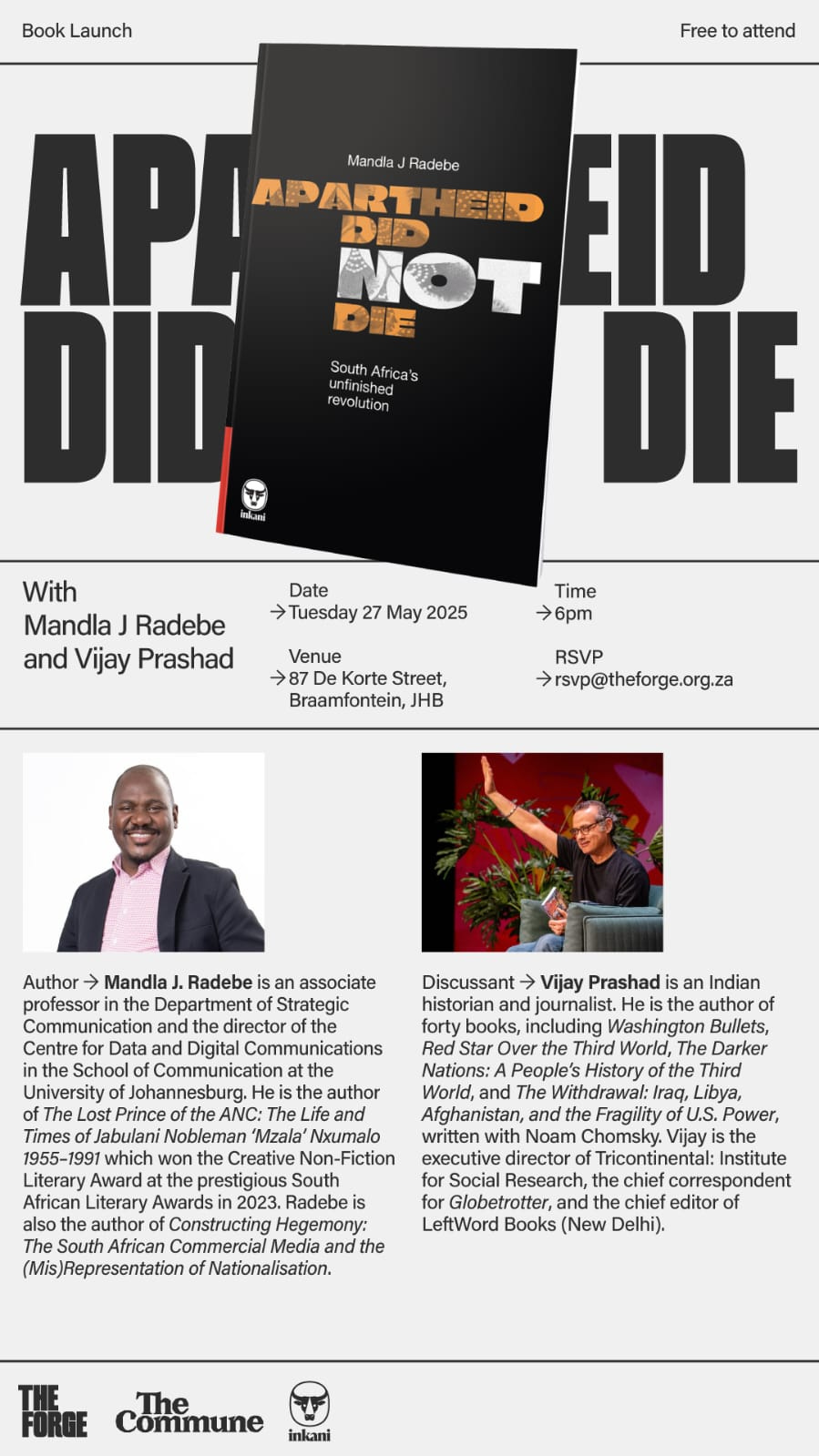

Apartheid ended in a negotiated settlement in 1994, thirty years ago. Professor Mandla J. Radebe has just released a new book, Apartheid Did Not Die, from Inkani Books (Johannesburg, 2025). If Ruth First had been alive, she would have written its foreword and been there at the release on May 27 at The Commune/The Forge in Johannesburg.

In parallel with the writers who were so important in spreading truth, (as Vijay Prashad is today), other truths are spread in many ways.

As a very young person looking through my father’s records I found three which have never left me. Sixty years on, not a month has gone by that I don’t listen to Leadbelly, Paul Robeson, and Miriam Makeba.

Makeba’s incredible voice softened the hard edges of people who would—and did—hate her for what she might have written. Just as Leadbelly’s voice (allegedly) freed him from a life sentence on Parchman Farm, and Robeson sang of things that would put him in jail then, and probably once again today. I believe in the power of art.

People often ask if there could be a Gazan Gandhi. We know the answer to that. And 200 Gazan Ruth First’s have been slaughtered in the past years. Others, like Richard Medhurst and Assange are being silenced. Is there a child there who could become a Gazan Miriam Makeba? Is that why they killed Hind Rajab?

Thank you for sharing this journalist’s so-important contribution to our collective freedom. As Simon Burke sang: “None of us are free if one of us is chained..”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eFkmRp_G2uo&pp=0gcJCdgAo7VqN5tD