This is a series on my favourite journalists, people whose bravery I admire but also whom I admire for their honesty and their way of recounting the news as they have experienced it and analysed it. I hope this set of essays will continue till I have run through the list of those whose books I have before me, who inspire me to report and to write.

#1 was on Odd Karsten Tveit, which you can read here.

I regret that I never got the chance to meet Wilfred Burchett (1911-1983).

I would never have known about him, because he has been largely disappeared from the debates and discussions about journalism and about the areas of the world that he covered. I found about Burchett one day when I was editing a piece by John Pilger (1939-2023) for Globetrotter. I said something to Pilger about a turn of phrase, and he said that it was similar to how Burchett put it. And so, he told me about his friend and told me to get the collection, Rebel Journalism. The Writings of Wilfred Burchett, edited by his son George (see some of his writings at Counterpunch) and by Nick Shimmin (2007), for which Pilger – Burchett’s student, in a sense – had written the foreword.

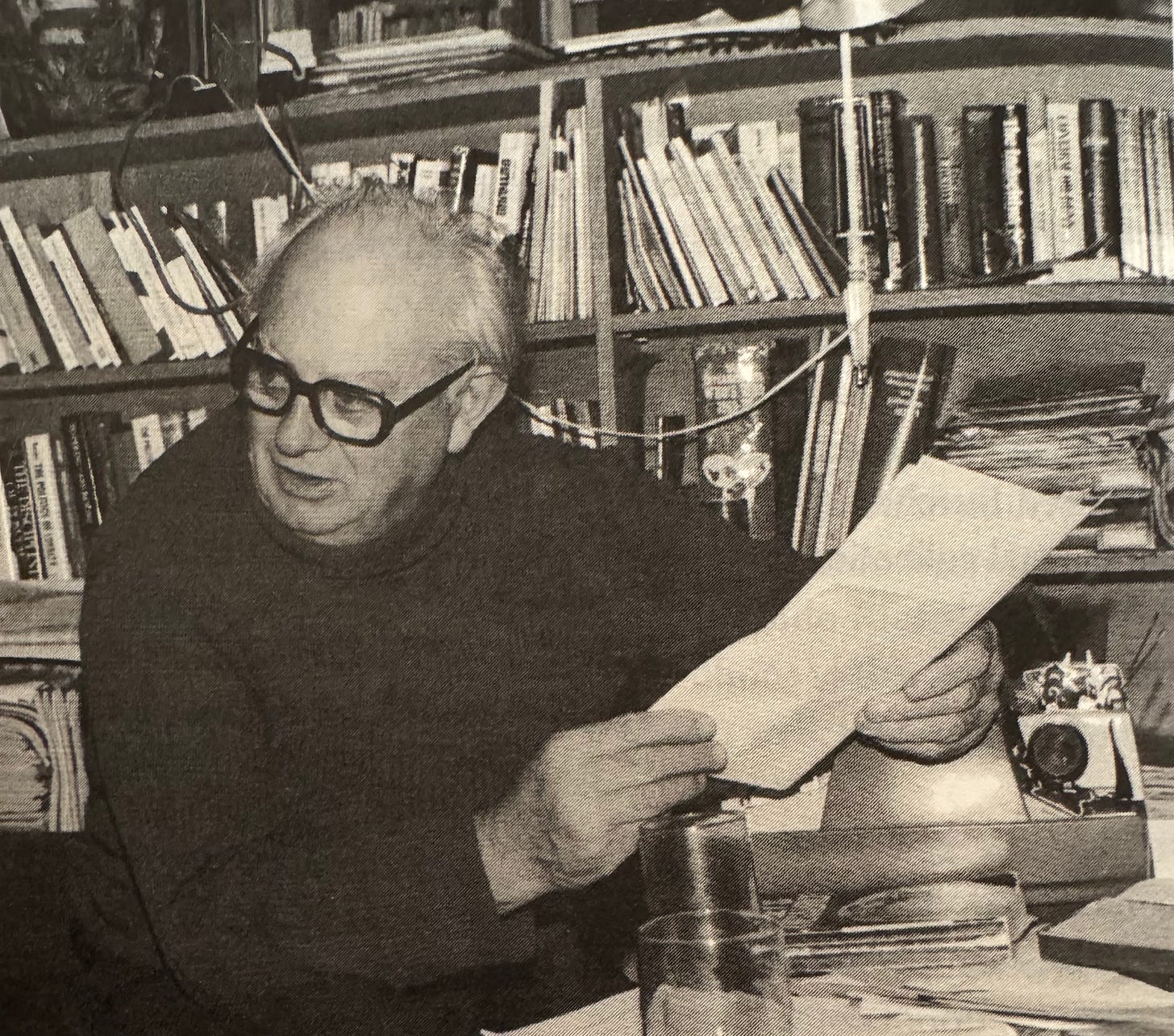

Wilfred Burchett in Meudon, France, the home of the Burchett family from 1968 to 1982.

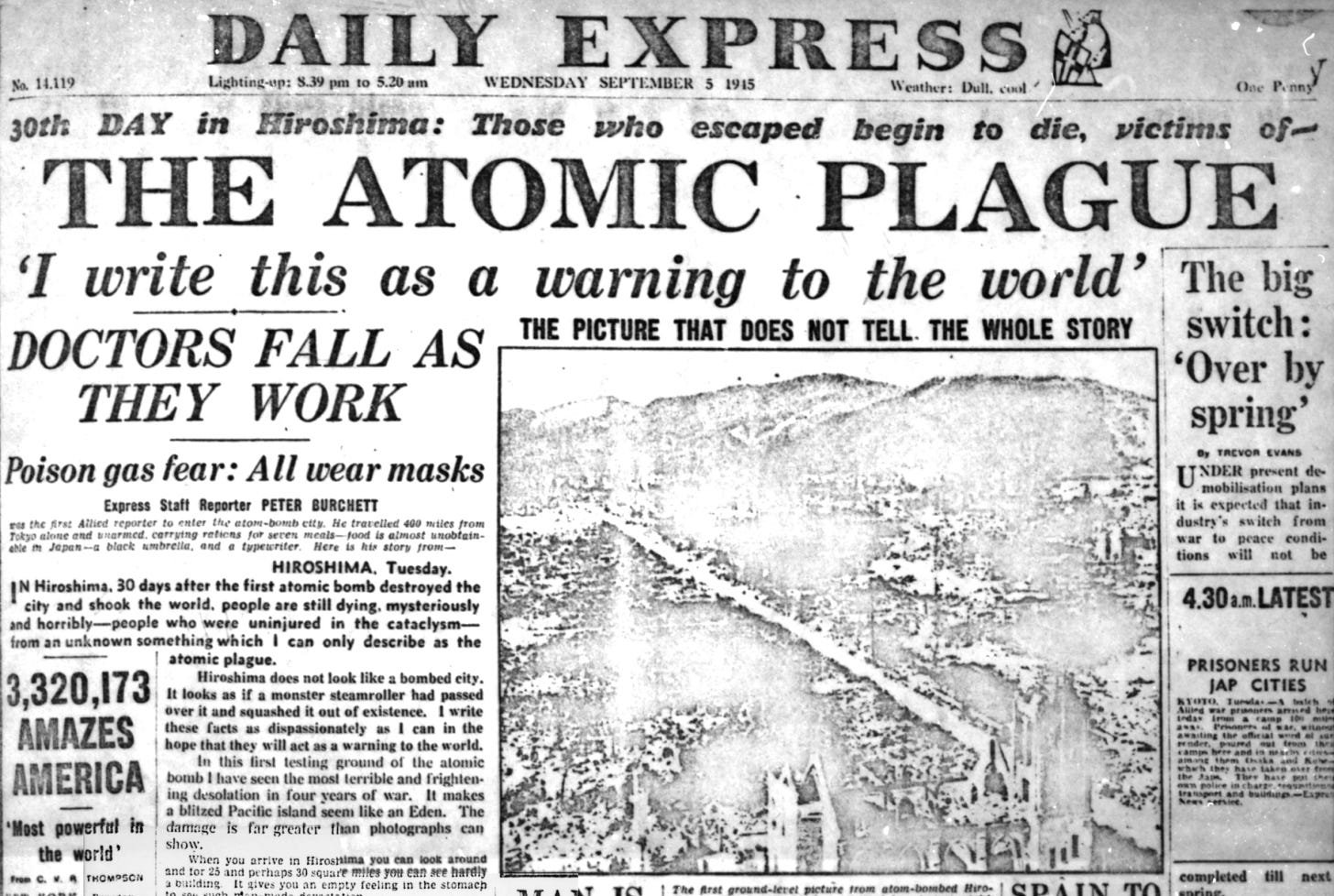

Never ignoring the advice of journalists with courage and craft, I went and got the book and read the pieces through from start to finish. The first story itself is remarkable. In August 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and then one on Nagasaki. Wilfred Burchett, a young Australian journalist in Okinawa, found his way – by stealth – to Hiroshima on 2 September, and broke the story of the impact of the bomb, and in breaking the story broke also the lies being told by the US authorities about what had transpired there. His article was published three days later in The Daily Express in London, titled, ‘I write this as a warning to the world’. There is a chilling sentence in the middle of the article that teaches you how to create sentences that are pregnant with meaning: ‘If you could see what is left of Hiroshima, you would think that London had not been touched by bombs’.

His most important byline was erroneously written as Peter and not Wilfred.

That first story made me a genuine admirer of the work of Burchett. But it did not end there. His story on Major Orde Wingate, known as the man who led Wingate’s Chindits (from Burmese, Chinthe, meaning lion) along the Burma Road campaign in the war against the Japanese. The essay forms part of Burchett’s book, Wingate Adventure. I can imagine Burchett, with his typewriter and camera, along that road that winds into China to cover not only this British-Indian operation but also the war of the Chinese against the Japanese. I wonder if along that road he met my relatives, including – for a brief time – my father (as a fireman), who were on that road as well. The style of the story reminded me a little of a Biggles novel, and so I was even further brought into Burchett’s world.

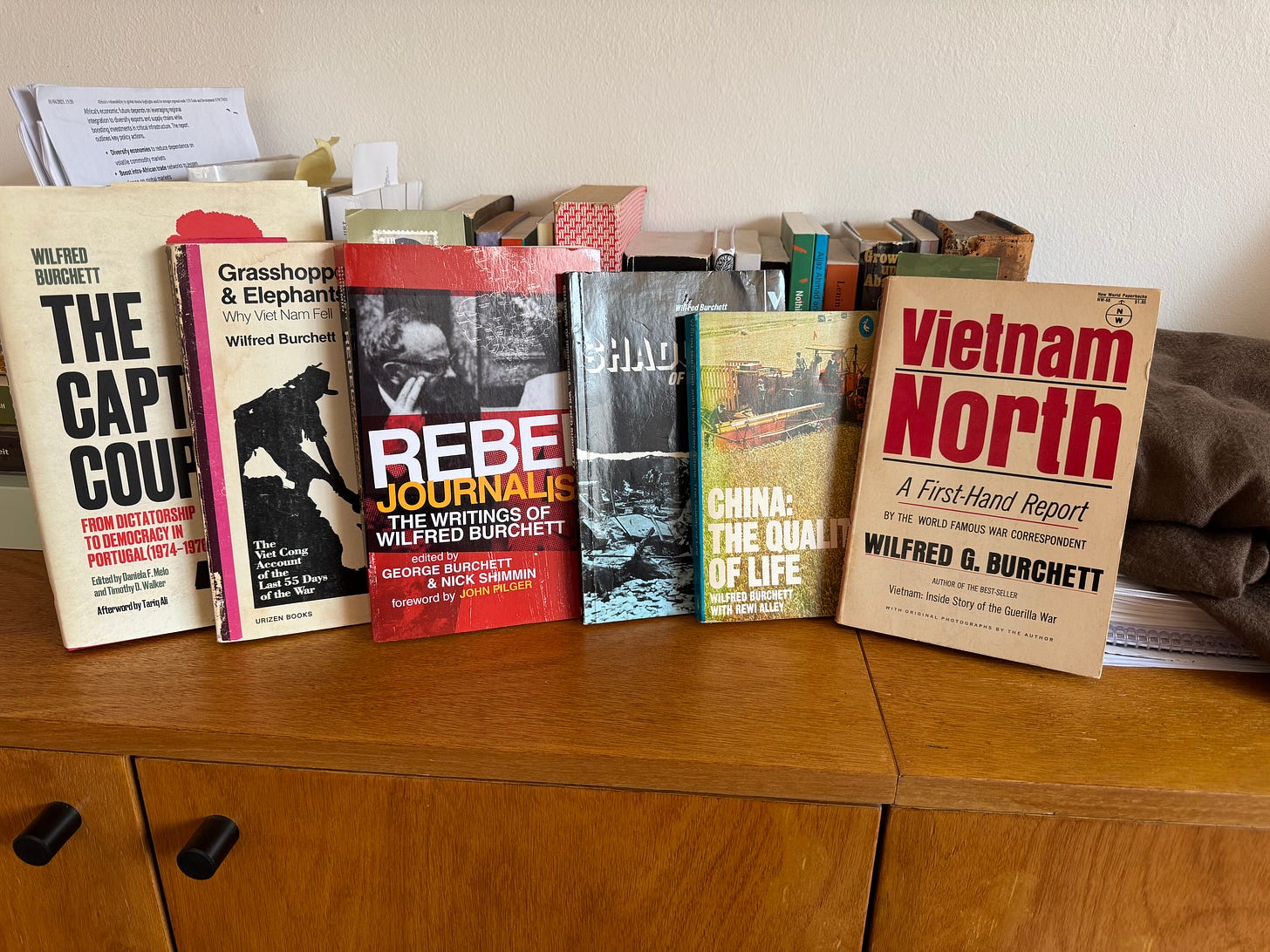

My Burchett books.

At a used book’s store in London, I found two of Burchett’s books that I have close to my heart (Vietnam North, 1966 and Grasshoppers and Elephants. Why Viet Nam Fell, 1976). Burchett decided to cover the US war on Vietnam not from Saigon like most Western journalists, but from the north. In February 1966 and April-May 1966, he travelled to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s capital in Hanoi and to the countryside, where the frontline lay. He met all the major leaders: Ho Chi Minh (my hero), General Vo Nguyen Giap, Le Duan, and others. In Vietnam North, he catalogues the work of maintaining a state and consolidating a society in a time of two decades of ceaseless bombardment by the United States (to learn more about Vietnam after the war, see my Globetrotter article from 12 May 2025 here).

Vietnam North is a portrait of the Vietnamese people, their leaders, and the institutions they struggled to build as they fought off the US imperialists. There is a paragraph in the midst of the book where you get a sense of the deep compassion of Burchett for the Vietnamese:

The Vietnamese women have accepted an enormous burden on their slim shoulders. Like the girl ammunition carrier at Ham Rong bridge, they all seem to be carrying twice their own weight. They have to replace the man at work in the field and factory but still be good mothers at home – and in many cases good children as well, for there are often the old people as well as the children to look after. To a certain extent, their burdens are eased by creches and nursery schools, but the war comes even there also. Normally the older women could look after the creches but when the planes come, strong, young people are needed to carry a whole armful of children at once, and move quickly. If there are not such strong, competent people in charge, mothers will come rushing back from the fields every time a plane is heard. All this means careful, rational organisation. I have seen creches in some villages where at the approach of a plane, babies are lowered on a cord and pulley device four at a time, each in separate padded baskets, into deep shelters located just under their normal resting place.

Such a description offers us a window into the concerns and challenges of the Vietnamese and the solutions they struggled to find to these concerns and challenges. This is pure Burchett, a people’s reporter who, yes, interviewed Ho Chi Minh, but then who also took the time to observe everyday life and interview village officials and fighters to learn about their own predicaments.

Ho Chi Minh, the farmer president.

If I was to teach a journalism class, I would use the chapter in Vietnam North called ‘Hanoi Computers’. Burchett says that in Washington, the Pentagon uses computers to process vast amounts of data on the war and on places to target and so on. But in Vietnam, in the absence of such technology, you have General Nguyen Van Vinh, who tells Burchett about his analysis of US war plans and how the Vietnamese counter them. His mind is sharp, and he remembers the smallest details but also keeps in mind the big picture. ‘Computer’ Vinh, as Burchett calls him, talks about how the US reliance upon helicopters ‘is itself a confession of the enemy’s weakness, his inability to open up and control communications or to occupy territory’. US troops did not want to be on the ground, and could not engage the Vietnamese on the ground successfully, so they turned to the air war, using B-52s (‘very inefficient’ in finding their targets) and helicopters.

If the Pentagon had read Vietnam North, and in particular the judgment of General Vinh, it would perhaps not have fought in Afghanistan for as long as it did – using aerial supremacy as a sign of strength, when in fact it is a sign of weakness, as ‘Computer’ Vinh told Burchett.

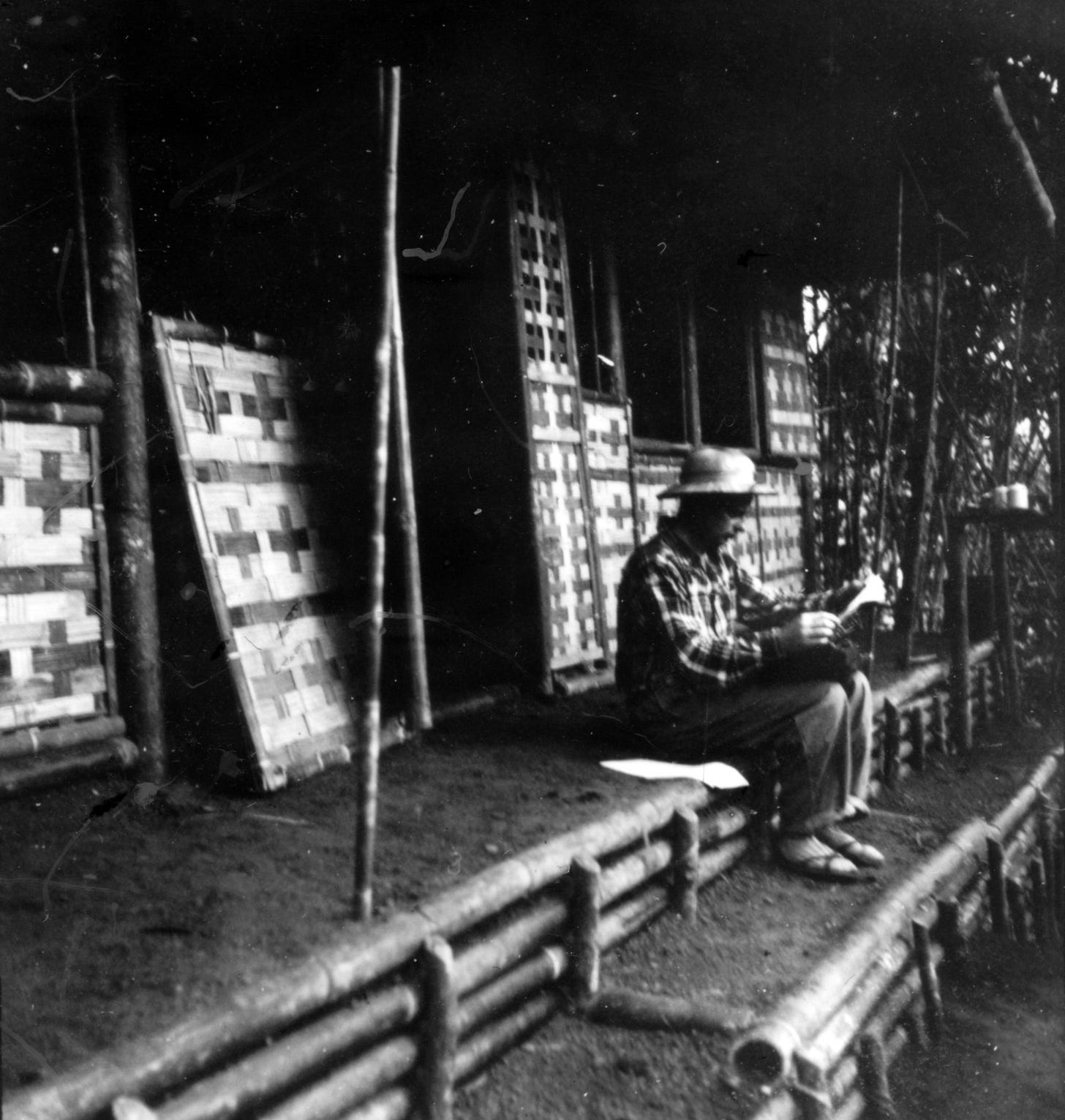

Burchett typing at Thai Nguyen in March 1954.

Verso has just published Burchett’s book on the Portuguese Carnation Revolution of 1976 (The Captain’s Coup: From Dictatorship to Democracy in Portugal, 1974-1976). I was given it by Oliver Eagleton – who runs the wonderful Sidecar blog – at the Verso office a few months ago (on a street that used to be a clandestine place for sex work). I have started it, but not finished it. It was written in English, translated into Portuguese, and then only published in that language.

The diligent editors – Daniela Melo (who teaches in Boston) and Timothy Walker (who teaches at UMASS) - went out and found the original manuscript. From what I have read, and I will continue to read it and write about it later, it is as wonderfully prescient as Burchett’s work on Vietnam.

Burchett with his wife Vesselina (Vessa) Ossikovska and Pham van Dong and Ho Chi Minh.

I hate it when they call someone ‘controversial’. I have tasted that epithet as well (once Forward offered me a compliment with the putdown: ‘as charismatic as he is controversial,’). It means only that the journalist is not along the grain of the powerful, but is telling the stories of those who are fighting to change the world. Some journalists are silenced by being killed (such as Shireen Abu Akleh, killed by the Israelis on 11 May 2022) and others are maligned (such as Gary Webb, who broke the story of the US government involvement in the cocaine trade). But the maligning is inflected by the class struggle. Burchett is a hero in Vietnam, he is maligned by Western and Australian regimes of power who lost the wars in Indo-China.

I am now working with George Burchett to bring out his father’s writings that have long been out of print. Keep an eye out for those books, which should be coming out – starting later this year.

First and foremost I would like to thank you for your serie on journalists, none of whom I knew of before. As a young man I participated in several demonstrations against the US war in Vietnam here in Copenhagen. During those days I awoke to the inhuman nature of capitalism. The demonstrations then were huge by danish standards, today it is different, in our weekly demonstration against the genocide perpetrated against palestinians it is the same 800 to 1000 persons that show up. Once a month we have a large demonstration where 5-8000 shows up, compared to the the anti US demonstrations in those days where 20.000 or more showed up, it is sad to see how few that participate.

Your work sharing these valuable historical yet neglected histories and commentaries is much appreciated. Thank you.

P.S. I have a couple of the Burchett books on Vietnam myself.